Socialism and Man in Cuba

- Sep 10, 2025

- 23 min read

by Ernesto Che Guevara

[ This article was written as a letter to Carlos Quijano, editor of Marcha, a weekly journal published in Montevideo, Uruguay. It was first published in Marcha and then in Verde Olivo , the official journal of the Revotuionary Armed Forces of Cuba, in April 1965.]

Dear comrade, * :

I conclude these notes on a trip through Africa, motivated by the desire to fulfill, albeit belatedly, my promise. I would like to do so by addressing the topic in the title. I think it might be of interest to Uruguayan readers.

It is common to hear capitalist spokesmen, as an argument in the ideological struggle against socialism, claim that this social system, or the period of socialist construction to which we are committed, is characterized by the abolition of the individual in favor of the state. I will not attempt to refute this assertion on a purely theoretical basis, but rather to establish the facts as they are experienced in Cuba and add some general comments. First, I will outline in broad strokes the history of our revolutionary struggle before and after the seizure of power.

As is well known, the exact date on which the revolutionary actions that culminated on January 1, 1959, began was July 26, 1953. A group of men led by Fidel Castro attacked the Moncada Barracks in Oriente province in the early hours of that day. The attack was a failure; failure turned into disaster, and the survivors ended up in prison, only to resume the revolutionary struggle after being amnestied.

During this process, in which only the germs of socialism existed, man was a fundamental factor. People trusted him, individualized, specific, with a name and surname, and the success or failure of the task at hand depended on his capacity for action.

The stage of guerrilla warfare arrived. This developed in two distinct environments: the people, a still-sleeping mass that had to be mobilized, and its vanguard, the guerrillas, the driving force of mobilization, generator of revolutionary consciousness and combative enthusiasm. This vanguard was the catalyst, the one that created the subjective conditions necessary for victory. Also in this era, within the framework of the proletarianization of our thinking, of the revolution taking place in our habits, in our minds, the individual was the fundamental factor. Each of the Sierra Maestra combatants who achieved a higher rank in the revolutionary forces had a history of notable achievements. These achievements were based on these achievements.

It was the first heroic era, in which they competed for positions of greater responsibility, greater danger, with no other satisfaction than the fulfillment of their duty. In our work of revolutionary education, we often return to this instructive theme. In the attitude of our combatants, we glimpse the man of the future.

On other occasions in our history, the total dedication to the revolutionary cause has been repeated. During the October Crisis or during the days of Cyclone Flora, we witnessed exceptional acts of courage and sacrifice carried out by an entire people. Finding the formula to perpetuate this heroic attitude in daily life is one of our fundamental tasks from an ideological perspective.

In January 1959, the revolutionary government was established, with the participation of several members of the traitorous bourgeoisie. The presence of the Rebel Army constituted the guarantee of power, a fundamental factor of strength.

Serious contradictions soon arose, initially resolved in February 1959, when Fidel Castro assumed the leadership of the government as Prime Minister. The process culminated in July of the same year, when President Urrutia resigned under pressure from the masses.

Role of the masses

A character that would be systematically repeated appeared in the history of the Cuban Revolution, now with clear characters: the masses.

This multifaceted entity is not, as is often claimed, the sum of elements of the same category (reduced to the same category, moreover, by the imposed system), acting like a docile flock. It is true that it unwaveringly follows its leaders, primarily Fidel Castro, but the degree to which it has earned that trust is precisely a result of its thorough understanding of the people's desires, their aspirations, and its sincere struggle to fulfill the promises made.

The masses participated in agrarian reform and the difficult task of managing state-owned enterprises; they lived through the heroic experience of Playa Girón; they were forged in the struggles against various CIA-armed bandits; they lived through one of the most important defining moments of modern times during the October Crisis; and they continue to work today to build socialism.

Viewed superficially, it might seem that those who speak of the subordination of the individual to the state are right. The masses carry out the tasks the government sets, whether economic, cultural, defense, sports, etc., with unparalleled enthusiasm and discipline. The initiative generally comes from Fidel or the high command of the revolution and is explained to the people, who take it as their own. At other times, local experiences are adopted by the party and the government to make them general, following the same procedure.

However, the State sometimes makes mistakes. When one of these mistakes occurs, a decline in collective enthusiasm is noted due to a quantitative decline in each of the elements that comprise it, and work is paralyzed until it is reduced to insignificant magnitudes; it is the time to rectify. This was the case in March 1962, in response to a sectarian policy imposed on the party by Aníbal Escalante.

It's clear that the mechanism isn't enough to ensure a succession of sensible measures, and that a more structured connection with the masses is lacking. We must improve it over the next few years, but for initiatives coming from higher levels of government, we're currently using the almost intuitive method of listening for general reactions to the problems raised.

Fidel is a master at this, and his particular way of integrating with the people can only be appreciated by watching him act. At large public gatherings, one observes something like a dialogue between two tuning forks, whose vibrations provoke new ones in the interlocutor. Fidel and the crowd begin to vibrate in a dialogue of increasing intensity until it reaches its climax in an abrupt finale, crowned by our cry of struggle and victory.

What is difficult to understand, for those who have not experienced the revolution, is the close dialectical unity that exists between the individual and the masses, where both interrelate and, in turn, the masses, as a group of individuals, interrelate with the leaders.

Capitalism and alienation

In capitalism, some phenomena of this type can be seen when politicians capable of achieving popular mobilization emerge, but if it is not a genuine social movement, in which case it is not entirely legitimate to speak of capitalism, the movement will live out the life of the person instigating it or until the end of popular illusions, imposed by the rigor of capitalist society. In this, man is governed by a cold order that usually escapes the realm of understanding. The alienated human being has an invisible umbilical cord that links him to society as a whole: the law of value. It acts in all aspects of life, shaping his path and destiny.

The laws of capitalism, invisible and blind to the common people, act on the individual without their realizing it. They only see the breadth of a seemingly infinite horizon. This is how capitalist propaganda presents it, seeking to draw from the Rockefeller case—true or not—a lesson about the possibilities of success. The misery that must accumulate for such an example to emerge and the sum of the depravity that a fortune of that magnitude entails are not reflected in the picture, and it is not always possible for popular forces to clarify these concepts. (A discussion might be appropriate here about how, in imperialist countries, workers are losing their international class spirit due to a certain complicity in the exploitation of dependent countries and how this fact, at the same time, erodes the fighting spirit of the masses in the country itself, but that is a topic beyond the scope of these notes.)

In any case, the path is presented with obstacles that, apparently, an individual with the necessary qualities can overcome to reach the goal. The prize looms in the distance; the road is lonely. Furthermore, it's a wolf's race: one can only reach it through the failure of others.

The individual

I will now attempt to define the individual, the actor in that strange and fascinating drama that is the construction of socialism, in his dual existence as a unique individual and a member of the community.

I think the simplest thing is to recognize its quality as something undone, an unfinished product. The defects of the past carry over into the present in the individual's consciousness, and continuous work must be done to eradicate them.

The process is twofold: on the one hand, society acts with its direct and indirect education; on the other, the individual undergoes a conscious process of self-education.

The new society in the making must compete very hard with the past. This is felt not only in the individual consciousness, which is burdened by the remnants of an education systematically oriented toward individual isolation, but also by the very nature of this transitional period, with its persistent commodity relations. The commodity is the economic cell of capitalist society; as long as it exists, its effects will be felt in the organization of production and, consequently, in consciousness.

In Marx's framework, the transition period was conceived as the result of the explosive transformation of the capitalist system, shattered by its contradictions. Subsequently, we have seen how some countries that constitute weak branches have broken away from the imperialist tree, a phenomenon predicted by Lenin.

In these countries, capitalism has developed sufficiently to make its effects felt, in one way or another, on the people, but it is not its own contradictions that, once all possibilities are exhausted, bring the system crashing down. The liberation struggle against an external oppressor, the misery caused by strange accidents, such as war, whose consequences place the privileged classes on the exploited, and liberation movements aimed at overthrowing neocolonial regimes are the usual triggering factors. Conscious action does the rest.

In these countries, a comprehensive education for social work has not yet been developed, and wealth is far from being within the reach of the masses through the simple process of appropriation. Underdevelopment, on the one hand, and the habitual flight of capital to "civilized" countries, on the other, make rapid change without sacrifice impossible. There is still a long way to go in building the economic base, and the temptation to follow the well-trodden paths of material interest as a driving force for accelerated development is very great.

Discarding the blunted weapons of the past

There is a danger that the forest for the trees may be hidden. Pursuing the dream of achieving socialism with the help of the blunted weapons bequeathed to us by capitalism (the commodity as the economic cell, profitability, individual material interest as a lever, etc.), one can reach a dead end. And one arrives there after traveling a long distance where the paths often intersect and where it is difficult to perceive the moment when one took a wrong turn. Meanwhile, the adapted economic foundation has done its undermining work on the development of consciousness. To build communism, simultaneously with the material foundation, one must create a new man.

Hence the importance of choosing the right instrument for mass mobilization. This instrument must be fundamentally moral in nature, without neglecting the proper use of material incentives, especially those of a social nature.

As I said, in times of extreme danger, it's easy to intensify moral impulses; to maintain their validity, it's necessary to develop a consciousness in which values acquire new categories. Society as a whole must become a gigantic school.

The broad outlines of the phenomenon are similar to the process of capitalist consciousness-raising in its early days. Capitalism resorts to force, but it also educates people about the system. Direct propaganda is carried out by those charged with explaining the inevitability of a class regime, whether of divine origin or imposed by nature as a mechanical entity. This appeases the masses who find themselves oppressed by an evil against which struggle is impossible.

Next comes hope, and this is how it differs from previous caste regimes that offered no possible way out.

For some, the caste formula will still be valid: the reward for the obedient is arrival, after death, in other wonderful worlds where the good are rewarded, thus continuing the old tradition. For others, it is innovation; class separation is fatal, but individuals can escape the class they belong to through work, initiative, etc. This process, and that of self-education for success, must be profoundly hypocritical: it is the self-serving demonstration that a lie is true.

In our case, direct education takes on much greater importance. The explanation is convincing because it's true; it requires no subterfuge. It is exercised through the State's educational apparatus, based on general, technical, and ideological culture, by means of agencies such as the Ministry of Education and the Party's dissemination apparatus. Education takes hold among the masses, and the advocated new attitude tends to become a habit; the masses adopt it and exert pressure on those who have not yet been educated. This is the indirect form of educating the masses, just as powerful as the other.

The new man and a new consciousness

But the process is conscious; the individual is continually impacted by the new social power and perceives that he is not completely adequate to it. Under the influence of the pressure of indirect education, he tries to adapt to a situation he feels is just, and whose own lack of development has prevented him from doing so until now. He self-educates.

In this period of socialist construction, we can see the emerging new man. His image is not yet complete; it could never be, since the process runs parallel to the development of new economic forms. Leaving aside those whose lack of education leads them to take the solitary path, to the self-satisfaction of their ambitions, there are those who, even within this new panorama of collective progress, tend to walk isolated from the masses they accompany. The important thing is that men are becoming increasingly aware of the need to integrate into society and, at the same time, of their importance as its driving forces.

They no longer march completely alone, along lost paths, toward distant desires. They follow their vanguard, made up of the Party, the advanced workers, the advanced men who walk linked to the masses and in close communion with them. The vanguards have their sights set on the future and their reward, but this is not seen as something individual; the prize is the new society where men will have distinct characteristics: the society of communist man.

The road is long and full of difficulties. Sometimes, by straying from the path, we have to turn back; other times, by walking too quickly, we become separated from the masses; sometimes, by walking too slowly, we feel the close breath of those on our heels. In our ambition as revolutionaries, we try to walk as quickly as possible, opening up paths, but we know that we must draw nourishment from the masses and that they can only advance more quickly if we encourage them with our example.

Despite the importance given to moral incentives, the fact that there is a division into two main groups (excluding, of course, the minority of those who, for one reason or another, do not participate in the construction of socialism) indicates the relative lack of development of social consciousness. The vanguard group is ideologically more advanced than the masses; the latter are familiar with the new values, but insufficiently so. While the former undergoes a qualitative change that allows them to sacrifice themselves in their vanguard role, the latter only see things halfway and must be subjected to incentives and pressures of a certain intensity; it is the dictatorship of the proletariat exerted not only over the defeated class, but also individually, over the victorious class.

All of this entails, for its complete success, the need for a series of mechanisms, revolutionary institutions. The image of multitudes marching toward the future fits with the concept of institutionalization as a harmonious set of channels, steps, dams, well-oiled apparatuses that allow for this march, that allow for the natural selection of those destined to walk at the forefront and that award and punish those who serve or harm the society under construction.

This institutionalization of the Revolution has not yet been achieved. We are seeking something new that allows for perfect identification between the government and the community as a whole, tailored to the specific conditions of building socialism and avoiding as much as possible the commonplaces of bourgeois democracy, transplanted to the emerging society (such as legislative chambers, for example). There have been some experiments dedicated to gradually creating the institutionalization of the Revolution, but without too much haste. The greatest obstacle we have faced has been the fear that any formal aspect would separate us from the masses and the individual, causing us to lose sight of the ultimate and most important revolutionary ambition, which is to see man liberated from his alienation.

Despite the lack of institutions, which must be gradually overcome, the masses now make history as a conscious collective of individuals fighting for a common cause. Under socialism, man, despite his apparent standardization, is more complete; despite the lack of a perfect mechanism for this, his ability to express himself and make himself felt within the social apparatus is infinitely greater.

It is still necessary to emphasize their conscious participation, both individual and collective, in all mechanisms of management and production and to link it to the idea of the need for technical and ideological education, so that they feel how these processes are closely interdependent and how their progress is parallel. In this way, they will achieve full awareness of their social being, which is equivalent to their full realization as human beings, all the chains of alienation broken.

The role of labour

This will translate concretely into the reappropriation of their nature through liberated labor and the expression of their own human condition through culture and art.

For labor to develop in the first, it must acquire a new condition; the commodity-man ceases to exist, and a system is established that grants a quota for the fulfillment of social duty. The means of production belong to society, and the machine is merely the trench where duty is fulfilled. Man begins to free his thinking from the vexing fact of the need to satisfy his animal needs through work.

He begins to see himself portrayed in his work and to understand his human magnitude through the created object, the labor performed. This no longer entails leaving a part of his being in the form of sold labor power, which no longer belongs to him, but rather signifies an emanation of himself, a contribution to the common life in which he is reflected; the fulfillment of his social duty.

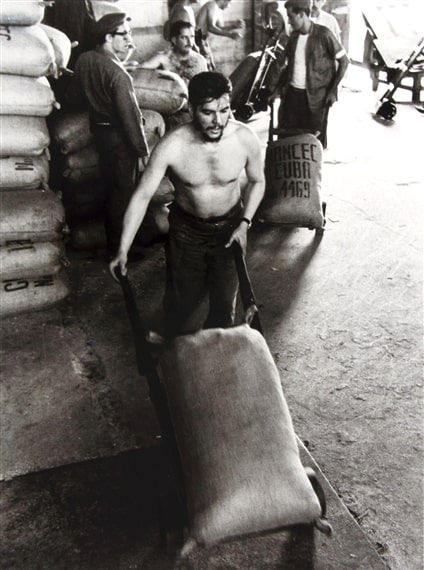

We do everything possible to give work this new category of social duty and to unite it with the development of technology, on the one hand, which will provide conditions for greater freedom, and with voluntary work on the other, based on the Marxist appreciation that man truly achieves his full human condition when he produces without the compulsion of the physical need to sell himself as a commodity.

Of course, there are still coercive aspects in work, even when necessary; man has not transformed all the coercion that surrounds him into a conditioned reflex of social nature and still produces, in many cases, under the pressure of his environment (moral compulsion, as Fidel calls it). He still needs to achieve complete spiritual recreation in his own work, without the direct pressure of his social environment, but bound to it by new habits. This will be communism.

Change doesn't happen automatically in consciousness, just as it doesn't in the economy. Changes are slow and not rhythmic; there are periods of acceleration, others of slowness, and even of decline.

We must also consider, as we noted earlier, that we are not facing a purely transitional period, as Marx saw it in the Critique of the Gotha Program , but rather a new phase he had not foreseen; the first transitional period of communism or the construction of socialism. This period takes place amidst violent class struggles and with elements of capitalism within it that obscure a full understanding of its essence.

If we add to this the scholasticism that has slowed the development of Marxist philosophy and prevented the systematic treatment of the period, whose political economy has not been developed, we must agree that we are still in its infancy and it is necessary to dedicate ourselves to investigating all the essential characteristics of the same before elaborating a more far-reaching economic and political theory.

The resulting theory will inevitably give precedence to the two pillars of construction: the formation of the new human being and the development of technology. In both aspects, we still have much to do, but the delay in understanding technology as a fundamental basis is less excusable, since this is not a matter of advancing blindly but rather of following, for a significant stretch, the path forged by the world's most advanced countries. This is why Fidel insists so insistently on the need for technological and scientific training for all our people, and even more so, for its vanguard.

Art and commodity production

In the realm of ideas that lead to non-productive activities, it is easier to see the division between material and spiritual need. For a long time, man has sought to free himself from alienation through culture and art. He dies daily during the eight or more hours he acts as a commodity in order to be resurrected in his spiritual creation. But this remedy carries the seeds of the same disease: he is a solitary being who seeks communion with nature. He defends his individuality, oppressed by the environment, and reacts to aesthetic ideas as a unique being whose aspiration is to remain immaculate.

This is merely an attempt at escape. The law of value is no longer a mere reflection of the relations of production; monopoly capitalists surround it with a complicated scaffolding that turns it into a docile servant, even when the methods they employ are purely empirical. The superstructure imposes a type of art in which artists must be educated. The rebels are dominated by the machinery, and only exceptional talents can create their own work. The rest become shameful wage earners or are ground down.

Artistic research is invented and held up as defining freedom, but this "research" has its imperceptible limits until it collides with them—that is, until it addresses the real problems of humankind and its alienation. Meaningless anxiety or vulgar pastimes are convenient outlets for human restlessness; the idea of making art a weapon of denunciation is opposed.

If you respect the rules of the game, you'll get all the honors you'd get if you invented tricks. The only condition is not to try to escape from the invisible cage.

When the Revolution took power, an exodus of the totally domesticated occurred; the rest, revolutionaries or not, saw a new path. Artistic exploration gained new impetus. However, the routes were more or less mapped out, and the meaning of the concept of escape was hidden behind the word "freedom." This attitude often persisted among the revolutionaries themselves, a reflection of bourgeois idealism in their consciousness.

In countries that underwent a similar process, attempts were made to combat these tendencies with exaggerated dogmatism. General culture became almost taboo, and a formally exact representation of nature was proclaimed the ultimate cultural aspiration. This later became a mechanical representation of the social reality they sought to portray: the ideal society, almost free of conflicts and contradictions, that they sought to create.

Socialism is young and has flaws.

We revolutionaries often lack the knowledge and intellectual audacity necessary to undertake the task of developing a new person through methods other than conventional ones, and conventional methods suffer from the influence of the society that created them. (Once again, the issue of the relationship between form and content arises.) The disorientation is great, and the problems of material construction absorb us. There are no artists of great authority who, in turn, possess great revolutionary authority. The members of the Party must take this task into their own hands and seek to achieve the main objective: educating the people.

The aim is then to simplify, to what everyone understands, which is what the officials understand. Authentic artistic research is nullified, and the problem of general culture is reduced to an appropriation of the socialist present and the dead (and therefore non-dangerous) past. Thus, socialist realism is born on the foundations of the art of the last century.

But the realist art of the 19th century is also class-based, perhaps more purely capitalist than the decadent art of the 20th century, where the anguish of alienated man is transparent. Capitalism in culture has given its all, and all that remains of it is the harbinger of a stinking corpse in art: its decadence today. But why try to find the only valid recipe in the frozen forms of socialist realism? One cannot oppose socialist realism with "freedom," because it does not yet exist; it will not exist until the full development of the new society. But one should not attempt to condemn all forms of art after the first half of the 19th century from the papal throne of uncompromising realism, for one would fall into the Proudhonian error of returning to the past, putting a straitjacket on the artistic expression of the man who is born and built today.

What is lacking is the development of an ideological-cultural mechanism that allows for research and clears out the weeds that are so easily multiplied in the fertile ground of state subsidies.

In our country, the error of realist mechanism has not occurred, but another sign of the opposite has. This has been due to a failure to understand the need to create a new man, one who represents neither the ideas of the 19th century nor those of our decadent and morbid century. The man of the 21st century is the one we must create, although it is still a subjective and unsystematized aspiration.

This is precisely one of the fundamental points of our study and our work, and to the extent that we achieve concrete successes on a theoretical basis or, vice versa, draw broad theoretical conclusions based on our concrete research, we will have made a valuable contribution to Marxism-Leninism, to the cause of humanity. The reaction against the man of the 19th century has brought us a return to the decadence of the 20th century; this is not a very serious error, but we must overcome it, otherwise we will open a wide path to revisionism.

Great multitudes are developing, new ideas are gaining momentum within society, and the material possibilities for the comprehensive development of absolutely all its members make the work much more fruitful. The present is a time of struggle; the future is ours.

In short, the guilt of many of our intellectuals and artists lies in their original sin; they are not authentically revolutionary. We can try to graft the elm tree to bear pears, but at the same time we must plant pear trees. New generations will come free of original sin. The chances of emerging exceptional artists will be all the greater the more the field of culture and the possibilities of expression have been broadened.

Our task is to prevent the current generation, dislocated by its conflicts, from becoming perverted and perverting the new ones. We must not create salaried workers docile to official thinking or "interns" who live under the protection of the budget, exercising a so-called freedom. The revolutionaries will come who will sing the song of the new man with the authentic voice of the people. It is a process that takes time.

Role of youth

In our society, youth and the Party play a role.The first is particularly important, as it is the malleable clay with which the new man can be built without any of the previous defects.

The youth are treated in accordance with our aspirations. Their education is increasingly comprehensive, and we don't forget their integration into the workforce from the very beginning. Our interns do physical labor during their vacations or while studying. Work is a reward in some cases, a tool for education; in others, never a punishment. A new generation is being born.

The Party is a vanguard organization. The best workers are nominated by their comrades for membership. This is a minority but has great authority due to the quality of its cadres. Our aspiration is for the Party to be a mass organization, but only when the masses have reached the vanguard level of development, that is, when they are educated for communism. And our work is directed toward that education. The Party is the living example; its cadres must teach lessons in hard work and sacrifice; they must lead the masses, through their actions, to the end of the revolutionary task, which entails years of hard struggle against the difficulties of construction, class enemies, the scourges of the past, imperialism...

I would now like to explain the role played by personality, by man as an individual among the masses that make history. This is our experience, not a recipe.

Fidel gave the Revolution momentum in its early years, direction, and a constant tone, but there is a good group of revolutionaries who develop in the same direction as the supreme leader, and a large mass of people who follow their leaders because they have faith in them; and they have faith in them because they have known how to interpret their aspirations.

It's not a question of how many kilograms of meat someone eats or how many times a year someone can go for a walk on the beach, or how many beauties from abroad can be bought with current wages. It's precisely a question of the individual feeling more fulfilled, with much greater inner wealth and much more responsibility.

The individual in our country knows that the glorious era in which he lives is one of sacrifice; he knows sacrifice. The first knew it in the Sierra Maestra and wherever there was fighting; later, we have known it throughout Cuba. Cuba is the vanguard of the Americas and must make sacrifices because it occupies the vanguard, because it shows the masses of Latin America the path to complete freedom.

Within the country, leaders must fulfill their vanguard role; and, it must be said with all sincerity, in a true revolution to which everything is given, from which no material reward is expected, the task of the vanguard revolutionary is both magnificent and agonizing.

Let me tell you, at the risk of seeming ridiculous, that the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love. It is impossible to imagine an authentic revolutionary without this quality. Perhaps it is one of the great tragedies of the leader; he must unite a passionate spirit with a cool mind and make painful decisions without a muscle spasm. Our vanguard revolutionaries must idealize this love for the people, for the most sacred causes, and make it unique, indivisible. They cannot descend with their small dose of daily affection to the places where the common man exercises it.

The leaders of the Revolution have children who, in their earliest years, don't learn to name their father; women who must take part in the general sacrifice of their lives to carry the Revolution to its destiny; the framework of friends strictly corresponds to the framework of the Revolution's comrades. There is no life outside of it.

Against dogmatism

Under these conditions, we must possess a great deal of humanity, a great deal of a sense of justice and truth, to avoid falling into dogmatic extremes, into cold scholasticism, into isolation from the masses. Every day, we must fight to ensure that this love for living humanity is transformed into concrete actions, into acts that serve as examples and as mobilization.

The revolutionary, the ideological driving force of the revolution within his party, is consumed by this uninterrupted activity that has no end but death, unless construction is achieved on a global scale. If his revolutionary zeal is dulled when the most pressing tasks are carried out on a global scale and proletarian internationalism is forgotten, the revolution he leads ceases to be a driving force and sinks into a comfortable slumber, exploited by our irreconcilable enemies, imperialism, which is gaining ground. Proletarian internationalism is a duty, but it is also a revolutionary necessity. This is how we educate our people.

Of course, there are dangers present in the current circumstances. Not only the danger of dogmatism, not only the danger of freezing relations with the masses in the midst of the great task; there is also the danger of the weaknesses into which one can fall. If a person thinks that, in order to dedicate his entire life to the revolution, he cannot distract his mind by worrying about a child missing a certain product, about the children's shoes being torn, about his family lacking a certain necessary good, he allows the seeds of future corruption to infiltrate this reasoning.

In our case, we have maintained that our children should have and lack what the children of the common man have and lack; and our family must understand this and fight for it. The revolution is made through man, but man must forge his revolutionary spirit day by day.

Thus we march. At the head of the immense column—we are neither ashamed nor intimidated to say so—comes Fidel, then the best cadres of the Party, and immediately behind, so close that their enormous strength is felt, come the people as a whole, a solid framework of individuals marching toward a common goal; individuals who have reached the awareness of what must be done; men who struggle to leave the realm of necessity and enter that of freedom.

This immense crowd is organizing itself; its order responds to the awareness of its necessity. It is no longer a dispersed force, divisible into thousands of fractions shot into space like grenade fragments, trying by any means, in a fierce struggle with their peers, to achieve a position, something that will provide support in the face of an uncertain future.

We know that there are sacrifices ahead of us and that we must pay a price for the heroic act of forming a vanguard as a nation. We, leaders, know that we must pay a price for the right to say that we are at the head of the people who are at the head of America. Each and every one of us duly pays our share of sacrifice, aware of receiving the reward in the satisfaction of a duty fulfilled, aware of advancing with everyone toward the new man who is looming on the horizon.

Let me try some conclusions:

We socialists are freer because we are more complete; we are more complete for being freer.

The skeleton of our complete freedom is formed; what is missing is the protein substance and the clothing; we will create them.

·Our freedom and its daily sustenance are the color of blood and swollen with sacrifice.

Our sacrifice is conscious; a price to pay for the freedom we build.

·The path is long and partly unknown; we know our limitations. We will create the man of the 21st century: ourselves.

We will forge ourselves in daily action, creating a new man with a new technique.

· Personality plays the role of mobilization and leadership insofar as it embodies the highest virtues and aspirations of the people and does not stray from the path.

The one who opens the way is the vanguard group, the best of the good, the Party.

The fundamental clay of our work is youth; in them we place our hope and prepare them to take the flag from our hands.

If this stammering letter clarifies anything, it has fulfilled the purpose for which I sent it.

Receive our ritual greeting, like a handshake or a "Hail Mary":

Homeland or death.

Comments